When I was 7 years old, my older brother brought home a game for our new PC. I wasn’t supposed to play it and that fact made me want to play it even more. I was already used to playing games like Crash Bandicoot and old DOS games like Prince of Persia, so I thought I was more than ready for another game. I was wrong.

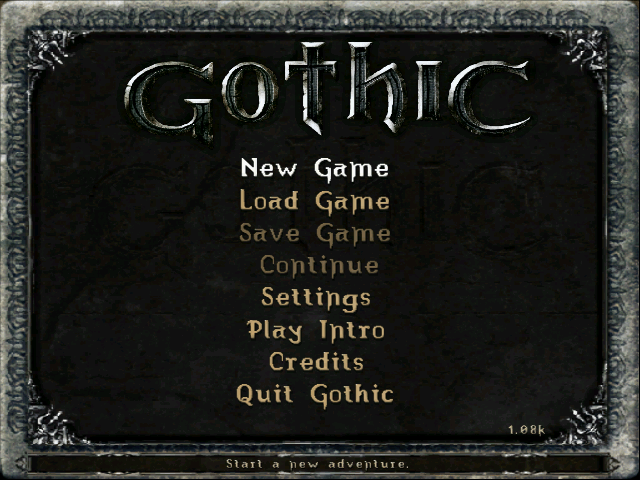

I put the disc in and booted the game up. A dark menu with GOTHIC written in intimidating letters slowly loaded. I started a new game and watched the introductory cutscene in awe. When the player character got thrown into the Mining Colony and I took control of him, I literally could not process what was happening. I thought games were simple – run, jump, collect some apples floating around. Now I was in a whole new world.

I remember the experience perfectly. I was absolutely terrified, slowly moving though this unfamiliar world and trying to figure out what was going on. The first enemy I encountered nearly killed me in real life via an untimely heart attack. I wandered through the colony, consumed by it.

This experience changed my life. I chased the high for years, bouncing from game to game trying to be so fully immersed again. It lead me to become a designer myself, trying to create something similar for others. In order to do that, though, I needed to understand it. How did I get so lost in Gothic and its world?

What is immersion?

According to the Cambridge dictionary it’s “the fact of becoming completely involved in something” and that definition conveys what most people imagine as immersion pretty well, but it’s a bit too vague to get any value from. Other game designers far more knowledgeable than I agreed on that point and much work has been done to understand what immersion is. I’ve come across fantastic research papers and books I’ll link in the sources delving into the subject, but I ran into the opposite problem while trying to apply the knowledge. The theories breaking down immersion go into such detail and try to cover so much ground they become very difficult to actually use in practice, at least for me. They didn’t give me the answer to what immersion is and how to achieve it.

The information I consider important from my research is as follows:

- Immersion comes from a combination of multiple sources

- Immersion in games is strengthened by interactivity

- Immersion is linked with the concept of flow

- Immersion happens when the border between the game and the player is blurred

Now I’ll attempt to answer the question myself. I believe that immersion happens when an action taken inside of a fictional world has an appropriate reaction according to the rules of said fictional world. That’s a mouthful, let’s break it down.

Fictional Worlds

I’ll borrow the term “magic circle” here. A fictional world is a sort of voluntary agreement between people. We step into the magic circle, where the real world ends and a fictional one begins, and we conduct ourselves according to the rules of the fictional world. If we break the rules, the illusion is broken.

A similar concept is also described as diegesis in storytelling. Everything included in a fictional narrative is diegetic – “inside” the fiction. The narrator of a story is an entity that tells the story, but never directly addresses the audience. Such an action would be what we commonly know as “breaking the fourth wall”, willingly breaking the unspoken contract between the performer and the audience.

Every form of media has a form of this unspoken agreement. When we step into the fictional world, be it a short comedic bit or a massive open world RPG, we willingly suspend our disbelief and act according to the world’s rules.

The Rules – Specified and Implied

Game designers are quite used to rules, but immersion is a bit more esoteric than just writing a good design doc and assuming we’re done. When it comes to immersion, fictional worlds have two types of rules, specified and implied.

Specified Rules

All rules that are specifically described by the fictional world. This is the kind of a rule every game designer understands, because it’s basically all we do. Every game mechanic, every tool given, even the objects and controls are a part of the ruleset for videogames. Tabletop games and sports have entire books describing how exactly the game is to be played. Game designers love specified rules, because they give us a degree of control over the experience.

Implied Rules

Fictional worlds exist on a scale ranging from abstract to realistic. The more realistic and thus closer to our human experience a fictional world gets, the more implied rules it will likely contain.

An abstract world is so unfamiliar to a human that it needs to be almost entirely governed by specified rules or we won’t be able to navigate it. A chess board is an abstract world that is very far removed from our monkey brains. We’re only able to interact with it via the specified ruleset and we have no preconceived notions about how it should function.

A realistic world borrows rules we know from our human experience without specifically describing them. The football field is a world that implies a whole lot. It implies we understand how physics work on some level, how to move, how to communicate, etc. A videogame that has humans present in its world implies an entire universe worth of rules. We understand that a human has emotions, can communicate, lie, eat, sleep and has evolved over billions of years on a suitable planet. All of this information is implied by the fictional world and should in theory be represented by it somehow.

All fictional worlds exist somewhere on this scale. The more abstract a world becomes, the more we have to specify how it functions. The more realistic a world becomes, the more we have to deal with implied rules of reality.

Action and Reaction

Now we’re finally getting to the good stuff. We know what a fictional world and its rules are, so where is the damn immersion? The feeling of being immersed in a fictional world comes from actions taken within it having an appropriate reaction. This ebb and flow is key to many aspect of game design and it’s absolutely crucial to immersion. Let’s explain this subject with an example.

In Gothic, you’re given a fairly simple quest – get rid off a man named Mordrag. It’s implied you should kill him, but it’s not specifically required. Gothic is an action RPG set in a world that’s essentially a fantasy prison, so killing someone is not exactly unheard of. The specified rules of the world allow you to fight Mordrag or talk to him. The implied rules of the world should let you do many things – threaten Mordrag, question him, kill him in his sleep or simply abandon the request. This is where Gothic shines and why it’s regarded as a very immersive game.

Gothic seems to be aware of these implied rules and reacts to your actions appropriately. If you want to threaten Mordrag, you can and he won’t like it. If you want to fight him, he’s happy to exchange blows. If you want to negotiate, a whole new story unravels where he agrees to leave the area and even help you out. All approaches have well thought out, immersive consequences after your task is done. Many paths that we assume should be possible are actually possible. Our actions are given an appropriate reaction, the fictional world shows its depth and the illusion is maintained or even strengthened.

This principle is applied everywhere. We assume that learning a new skill requires training because that’s what we know from our lives. Gothic acknowledges that implied rule and turns it into a specified one. Whenever you want to improve your character, you must find a trainer to teach you. Animations for eating, ambient NPC dialogue, realistic narrative design, the game just keeps responding to your inputs. The genre of immersive sims is particularly good at this behavior, hence the name. What you assume should be possible in the fictional world based on what you know about it is in fact possible.

That’s what immersion is. The player is presented with a fictional world, they express themselves in it and if the world react appropriately, they become more and more involved in it. Questions like “I wonder what happens if I do this” start to come up, as the player pushes the boundaries of the world, trying to find out where the illusion ends. They stop seeing the experience as “playing a game”. They are all in, experiencing a new world.

How to Create Immersive Design

I’ll provide 10 tips on how to use this knowledge while making a game, but the principle applies to any fictional world.

1. Know what rules you present

Write down as many specified and implied rules as you can about your game world and how you present them. You don’t have to go into too much detail, but you should be able to address an obvious rule with a simple explanation. You should also make sure you describe specified rules to the player well. The more they understand them, the more they will be inclined to experiment with them.

2. Decide which implied rules to address

A 3D space automatically implies the possibility of vertical movement, a humanoid character implies communication, one monster implies an ecosystem. It can be difficult to figure out which implied rules should be addressed and which could be left alone. Addressing every single implied rule could easily inflate your scope to astronomical heights. Consider approaching this task as maintaining a balance. Players are willing to suspend their disbelief if they’re already immersed. Gothic uses an infinite inventory, something that’s clearly not believable, but because the rest of the game is so immersive the player doesn’t dwell on it. Pick your battles and guide the player’s attention.

3. Immersion isn’t realism

To continue point no. 2, some implied rules not only can be ignored, but they absolutely should be. Your goal as a game creator isn’t perfect one-to-one realism, it’s making a fun game. Humans have to eat to survive, we have to maintain our hygiene, sleep, drink water and even the best marathon runners can’t jog everywhere. Games have to ignore these implied rules of the world, because they’re simply not fun. Immersion isn’t realism. You’re trying to transport the player into a fictional world, not make a new boring reality for them.

4. Immersion scales

You can apply these techniques on every scale of a game. How a game’s world and narrative design work with immersion may be quite obvious now, but even something as “simple” as swinging a sword benefits from the approach. How many rules of the world are implied when the player character swings a sword? Physics, weight distribution, physique of the character, level of expertise, exhaustion, magical powers – these are not only technical questions an animator must consider, they are implied rules a designer must wrestle with to immerse the player. We sometimes hear that a game feels good to play. That often means the player is experiencing joy from the mechanical execution of the gameplay, but also a feeling of the game responding to their actions exactly as it should within its world.

5. Immersion comes from a combination of sources

When you use immersion in multiple places and on multiple scales while creating a game, combining them has the greatest effect. Gordon Calleja describes 6 types of involvement that can lead to immersive design in his paper called From Immersion to Incorporation – kinesthetic, spatial, shared, narrative, affective and ludic. These 6 areas describe how certain aspects of a game can draw a player in. If you pay attention to how all parts of your game use immersion, you can combine them into a perfect mix that maintains the illusion much better than just a few isolated systems.

6. Implied rules can be turned into specified rules

If you run into problems with countless implied rules, you can often turn them into specified rules to handle them easier. If you’re worried that giving the player an infinite inventory like Gothic does will break their immersion, you can introduce the inventory as an object. Give the player a magical Bag of Holding, a small pouch the player model has attached to their waist that is enchanted to hold an infinite amount of stuff. This approach also doubles as a tutorial to how the inventory works, which might be handy. Monster Hunter World introduces its map and journal in this “diegetic” way, for example.

7. Appropriate doesn’t mean expected

When I say that every action needs an appropriate reaction within a fictional world to feel immersive, it doesn’t mean the player should always expect or understand it at first glance. The action and reaction flow is bound by the rules of the fictional world and the player might not understand those rules. That’s completely OK. You should strive to maintain internal consistency, the player figuring things out is part of the joy. Outer Wilds is a game that is structured entirely around not presenting its rules to the player up front, forcing them to find everything themselves, which leads to an incredible sense of discovery. The precious “aha!” moment comes from figuring out how the internal rules of a world function, piecing them together and mastering how to apply them.

8. Limits can be inspiring

Wrestling with immersive design can lead to very creative ideas. If you’re having trouble trying to address all rules your world presents, try to think outside the box. When I was designing a quest called Hooves and Horns for an RPG called Dungeon Realms, I ran into several issues. I needed the players to stay confined in a forest clearing. I couldn’t force them by saying “this is where the story takes place, stay here”, because my fictional world and ruleset allowed them to simply leave at any point. Forcing them to stay without reason would instantly break immersion. I ended up designing a series of endless combat encounters and challenges that triggered when they tried to leave. The combat implied the enchanted forest is keeping them in the clearing by force. This approach worked within the world and acted as an interesting clue – the players discovered the forest is somehow enchanted.

9. Subversion can be awesome

Immersion isn’t the ultimate goal of game design, fun is. Creating experiences that break the fourth wall, address the player and have fun with the format can be incredible. You can achieve subversion using immersion, however, so the techniques given here are still useful. A subversive game is aware of its rules and uses them as a leverage to surprise players. If your world has a player character that somehow regenerates health without any explanation, you can have an NPC comment on how absurd the fact is instead of explaining it. Calling attention to the flawed logic breaks immersion, telling the player “I, the designer, know you’re playing my game”. The Stanley Parable is one of the best known games that are built entirely around subversion.

10. Push deeper

As a final tip, I want to encourage you to explore your fictional world and make it deeper. If you introduce a new rule, always try to follow the logical consequences it will have within your already established rules. If your world has realistic physics, your jump mechanic should reflect it. The animation should include a landing based on height, it should change when the player collides with an object, and maybe you should include a sound effect indicating the character is exuding effort to overcome gravity. All of these details sound obvious, but if you don’t follow the chain of events, you might miss some. If your game has only 4 mechanics, it already has countless combinations of them if you’re willing to dig deeper and connect them together. Action and reaction, always.

The Magic Trick

After years of work I think I understand why Gothic made such an impact on me. It was a perfect storm, because the game is incredible at immersive design and I was a child with no understanding of how videogames function. It was like watching an amazing magician perform a show. An adult knows everything is fake, but they want to be fooled. They suspend their disbelief and enjoy the ride. A child might still believe the trick is real; they believe in magic.

Gothic’s internal consistency and masterful focus on which implied rules to address and how was so well executed, its fictional world seemed real to me. The illusion was almost perfect. Replaying the game now as an adult and a designer reveals how the sleight of hand is performed. I know what the magician is doing, but I can’t help buying into the trick over and over. Walking down to the Old Camp still makes my heart race every time.

I hope you found something useful in my rambling. I originally planned to make my first post fairly simple, but it just kept on going. I expect that my future stuff on here will be similar, so if you enjoyed this first entry, feel free to stop by again or check out the breakdown of my own work over in my portfolio. See you around.

Resources

If you have time, enjoy reading these. With some books I single out chapters that helped me with understanding immersion in particular, but you should really read the entire thing if you can.

- Slay the dragon: writing great video games by Robert Denton Bryant and Keith Giglio

- From Immersion to Incorporation by Gordon Calleja

- Diegesis and designing for immersion by Gabriel Naro

- The Art of Game Design by Jesse Shell – chapters 9, 10, 14 and 15

- Complete Kobold Guide to Game Design – chapter 13 by Wolfgang Baur

- A Theory of Fun for Game Design by Raph Coster – chapters 2 and 3